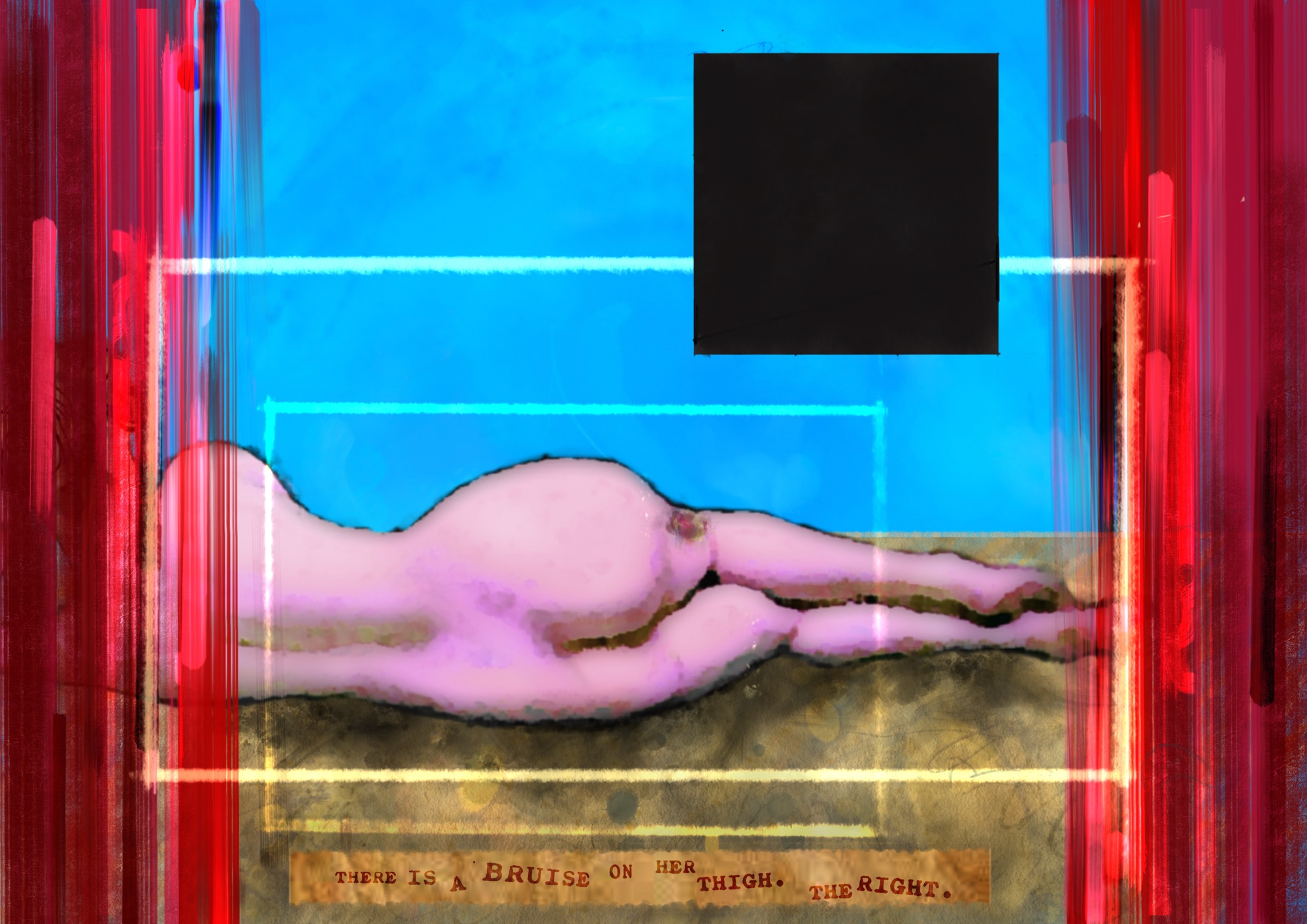

This is one of many things — pencil sketches, watercolors, oil paintings, a script for a short film — that I have made over the years that were inspired by Donald Barthelme‘s experimental short story, The Explanation. The “story” is written in a Q & A format, without any of the expected markers of time, place, or character. Just the dialogue between two “speakers,” designated as Q and A, The conversations range from discussions relating to a new, groundbreaking technology, to parody of academic discourse, to simple, declarative sentences that could come from an ESL class, to more personal matters. The title of the piece above comes from the latter: a recurring thread that suggests (among other things) a jealous husband interrogating a private detective about the activities of an unnamed woman:

Q: Do you see what she’s doing?

A: Removing her blouse.

Q: How does she look?

A: Self-absorbed.

[…]

Q: Well, what is she doing now?

A: Removing her jeans.

Q: What is she wearing underneath?

A: Pants. Panties.

Q: But she’s still wearing her blouse?

A: Yes.

Q: Has she removed her panties?

A: Yes.

Q: Still wearing the blouse?

A: Yes. She’s walking along a log.

Q: In her blouse. Is she reading a book?

A: No. She has sunglasses.

Q: She’s wearing sunglasses?

A: Holding them in her hand.

Q: How does she look?

A: Quite beautiful.

After jumping in quick succession between several other conversations, Barthelme returns to the one quoted above:

Q: What is she doing now?

A: There is a bruise on her thigh. The right.